Black Mountain: The People Who Fed Me

I first “met” Dr. Cynthia Greenlee in the pages of a magazine article, and because of her, I can never look at grits the same way again. Not too long afterward, we met in person and began a friendship. Cynthia doesn't believe in small talk. As an award-winning journalist, editor, scholar and leader, she says, “I want to capture sweetness and harm, sometimes in the same pieces. I need to show that the present is always in bed with the past.”

I was born near Asheville and Cynthia has roots in Black Mountain. One night, over an outdoor dinner in the cool Appalachian evening, we discussed what it’s like to grow up in this region: its beauty and complexity, why some stories get told and other stories get buried. Knowing our Blue Ridge & Black Mountain collections were joining East Fork this fall, I asked Cynthia if she would be interested in telling those stories we don’t often hear in the mainstream, the stories that have helped build the foundation of this place we call home. I’m so grateful she said, “Yes.”

This season, Cynthia will be leading us through an exploration of her Black Mountain—past, present, and future.

– Catherine Campbell, Senior Manager of Partnerships

It was at Aunt Lene and Uncle Marvin’s wood-paneled two-bedroom home that I learned everything I needed to know about Appalachian food: its inclination toward preservation, its hunting-forward larder, home gardens and home cooking, a do-it-yourself ethos because the government often paid no-never-mind to what happened in the hills.

The refrigerator in their Black Mountain home was perpetually and neatly stacked with full Tupperware; the outdoor refrigerator in the garage, stuffed with trout and venison (when I wrote a viral New York Times piece about second fridges, I was thinking of my Black, mountain or otherwise rural kinfolk). I’d sit at the kitchen table, crumble cornbread and mix it with strawberry preserves, my ad hoc cobbler. You could sit on the back porch and see Uncle Marvin's cucumbers bulging green in the summer light.

I've often quipped to friends that the "Black" in Black Mountain didn't apply to us, the small community of African-Americans in this hamlet about 20 miles east of Asheville (it refers to the surrounding shadowy peaks).

But every generation reclaims words and place names for itself, and I tell myself that we — my family, the descendants of enslaved people — made Black Mountain and its surrounding towns the cute, tourist-pandering area that it is. For the Black Mountain you know, if you’ve been there or you’ve bought pottery bearing its name, this picturesque hamlet of breweries, pottery, and gift shops aplenty is not quite the place I know.

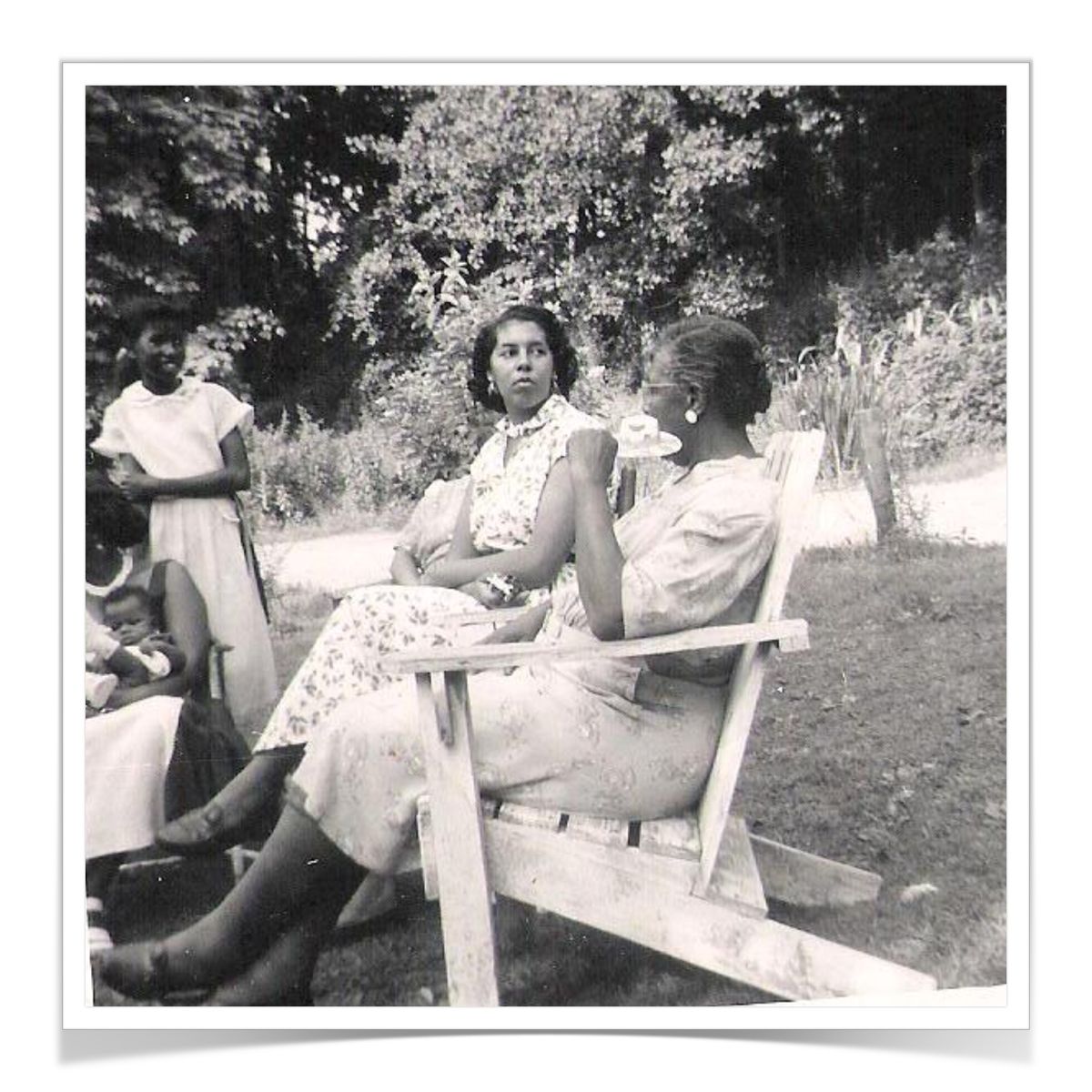

Aunt Erlene "Lene" Hamilton (facing viewer), extraordinary cook, probably at a family cookout or post-church meal

If labor and love make a place yours, surely we qualify as spiritual owners, even in this place that is not urban but gentrifying. My great-great grandmother, Myra, was enslaved by one Joseph Stepp, and in bondage she served visitors to his inn — and bore his children. The Black Mountain of my forebears, including the largely Black district along Cragmont Road, is now a curving street of tony houses — $400,000 and up — that replaced the modest homes Black residents built or expanded by hand and help. Up the street is the Thomas Chapel AME Zion Church site, now on the National Register of Historic Places and founded by formerly enslaved people who shared my DNA; a sky-blue Masonic lodge where our family often had our holiday pigouts; and a Montessori school that was once the segregated Carver elementary school for “Negro” children. Streets bear the names of Black families who held court in the town, and the skate park was similarly named after my aunt, Elizabeth “Lib” Harper, for her decades of community voluntarism.

In some ways, Black Mountain — vibrant, artsy town it is — is a ghost town for me: buildings that once housed my people and instead hold a history that is, like in many other Black Appalachian communities, in danger of being wiped away by new development and outmigration.

The last long porch talk I had with my Uncle Marvin, he told me that he wasn’t sure that anybody would remember who had been there before, his small house encircled by Arts and Crafts bungalows-McMansions. I started to assure him, but didn’t.

But never one to dwell too long on the negative, he waved me into the house and ambled to his backyard. I worried because the temperature was approaching 90 on this summer day, and so was my octogenarian uncle.

From a distance, I saw him bend and part squash vines rapidly colonizing his postage stamp-sized garden. I sat down at the table where I fiddled with a jar of peppers in vinegar and thought about all the times I'd seen my uncle and daddy douse it on their turnip greens. Wondered idly if the vinegar was as old as me.

This is the place my father called home. To be Black and Appalachian — some prefer the term Affrilachian, coined by Kentucky poet Frank X Walker — is to be a numerical minority and something of a demographic curiosity. Black Mountain itself is only about 7 percent African-American.

But it is the place that I learned that to love someone is to cook for them. Or to offer them unhampered access to your refrigerator. Years after Aunt Lene and Uncle Marvin passed away, I think of their refrigerator as “the welcome refrigerator.” They were supremely unbothered if I rummaged around for an orange soda, leftovers, or an ice cream sandwich. It was the height of hospitality.

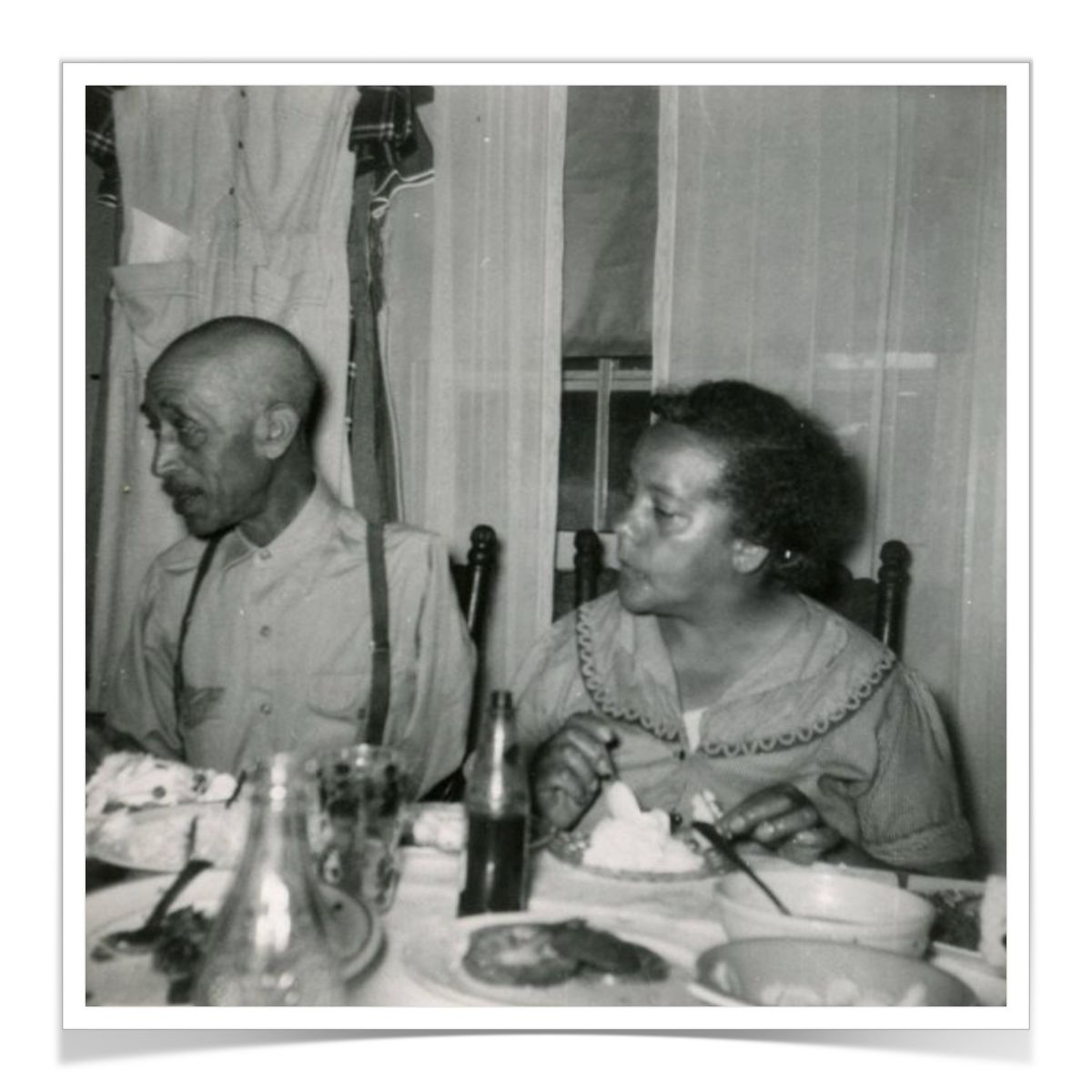

The author’s grandparents, James Hezekiah Greenlee and Grace Stepp Greenlee, at the table

We never ate out in Black Mountain. My parents, my two sisters, and I did a pilgrimage to each of my aunts' homes in our powder-blue Caprice Classic station wagon.

The visit order could never deviate, at great risk of offending a sister. Aunt Marvin and Aunt Lene's was first stop. There, my father's favorite sister, her long hair braided in a shiny pineapple atop her head, served him pinto beans, a lemon pie with a meringue pompadour and sweet tea so sugary diabetics couldn't glance in its direction. Nothing was too much for the favorite son.

Next was Aunt Lib's, if we could track her down at the Chamber of Commerce; she'd been a near-vegetarian most of my life but always bought a conciliatory bucket of chicken for the carnivores on the family tree. Aunt Margaret kept her downstairs refrigerator stocked with sodas. The oldest and sweetest of the Greenlee aunts, Hannah always seemed to have a pound cake in the kitchen, which became an Entemann's pastry when she languished from cancer.

We’d try to catch Grandma Grace, who wrote poetry for her grandchildren’s birthdays, and road-running Aunt Pansy whenever we could, and giggle at her chihuahua, who ate tomatoes and only tomatoes with tiny-canine gusto. Later, when Aunt Dot moved back from Atlanta, she’d try to balance our roadtrip menu with fruit and salmon.

As a very small child, I struggled to keep up with my father's gaggle of sisters — which had included two sets of twins — and I struggled equally with the expectation that no matter how full I was, I needed to eat a nibble at each house to please them all. But I came to know them by their food, their tables laden with dishes seasoned by affection.

The last back-porch talk I had with Uncle Marvin, I asked why his eyes kept darting to his backyard.

“I was checking my rabbit box. I think I’ve got one,” he said

"What are you going to with it?"

He was kind enough to not point out this was, perhaps, a dumb question.

"I'm going to eat it."

I blinked. "You’re going to kill it?" He widened his eyes in return. "Shoooot,” drawing out the vowel, and sucking his teeth. “That has to come before you eat it.”

He talked about how he, my father, and his brothers roamed these woods when their hair was full and their legs were fresh. One of his brothers earned the moniker Kill Pretty because his aim was so sweet, so precise he could shoot anything out of a tree: raccoon, squirrel, what have you.

I left Uncle Marvin before the rabbit met kingdom come, before he cut little slits behind its head and pulled back its pelt like a furry banana skin. The next day, I fetched a foil-wrapped package of fried rabbit. It didn’t taste like chicken. But it did taste like love.