Update on How Our Pots Get Made

East Fork’s manufacturing floor stands on the precipice of a big change. We’re preparing to move to a new clay body and glaze recipe that’s been three years in the making.

Read more

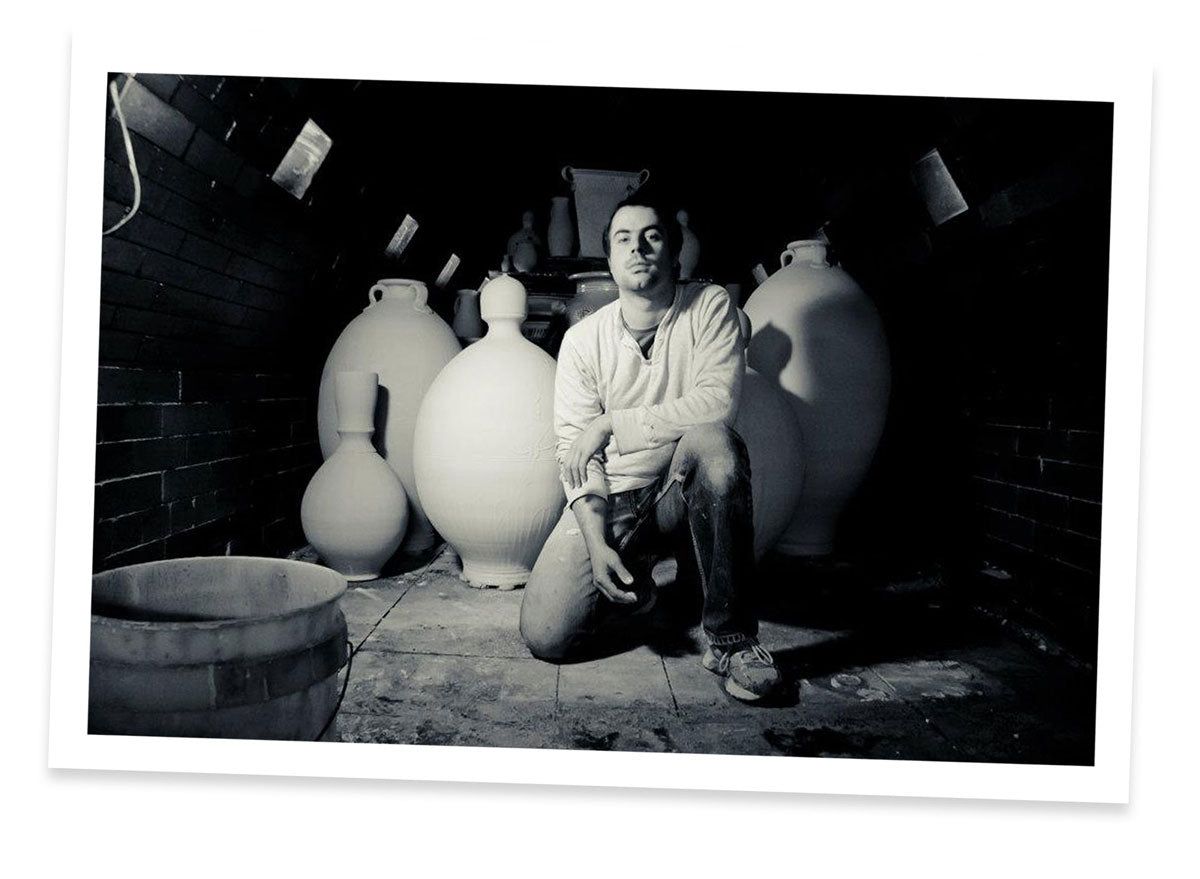

Why Is It Called East Fork?

Alex Matisse, East Fork’s founder, on how the company got its name and why it represents a “little private victory” for him.

Read more

Color Theory: Core Colors

Our Head of Design, Nicole Lissenden, shares the details of how we built our core color palette.

Read more

How We Make The Mug

Want to know everything there is to know about how we make The Mug? It’s your lucky day. Get the behind-the-scenes on how we make our iconic ceramic mug.

Read more

Update on How Our Pots Get Made

East Fork’s manufacturing floor stands on the precipice of a big change. We’re preparing to move to a new clay body and glaze recipe that’s been three years in the making.

Read more

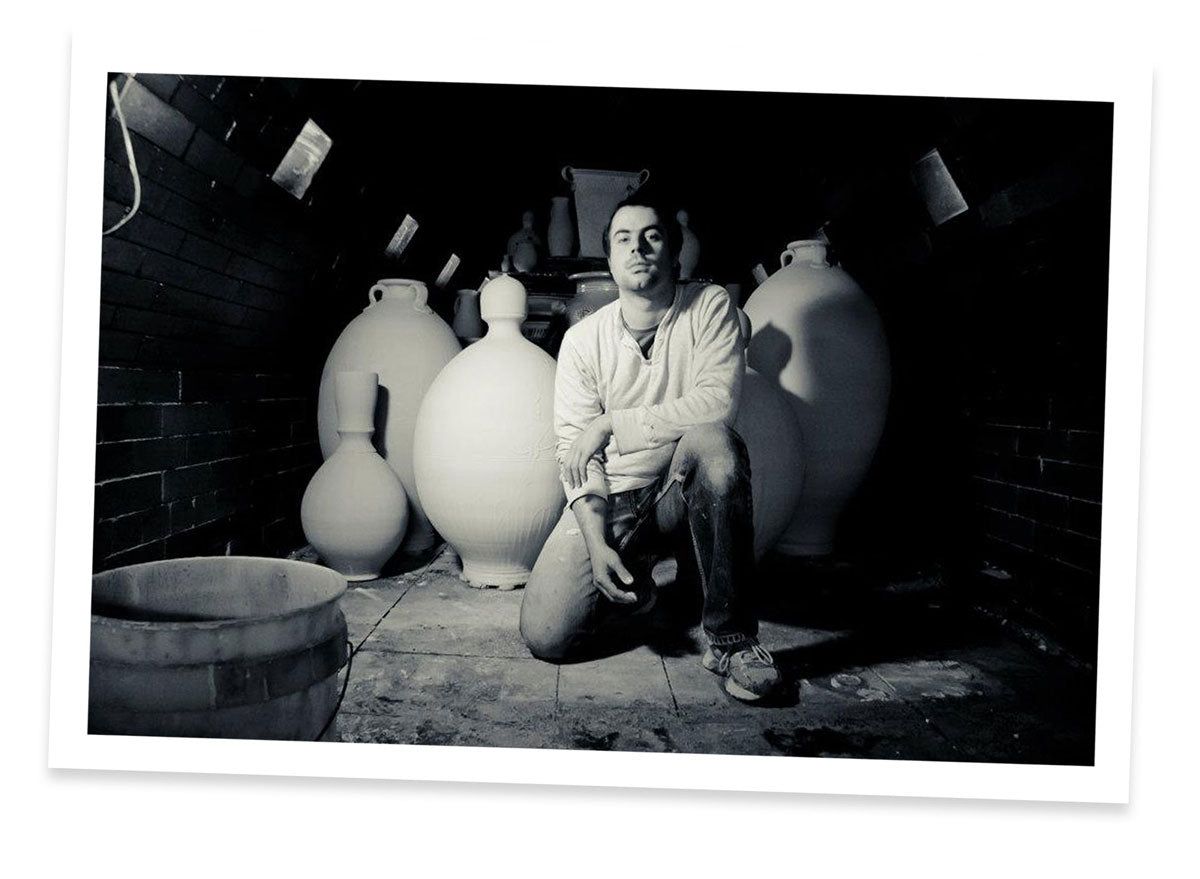

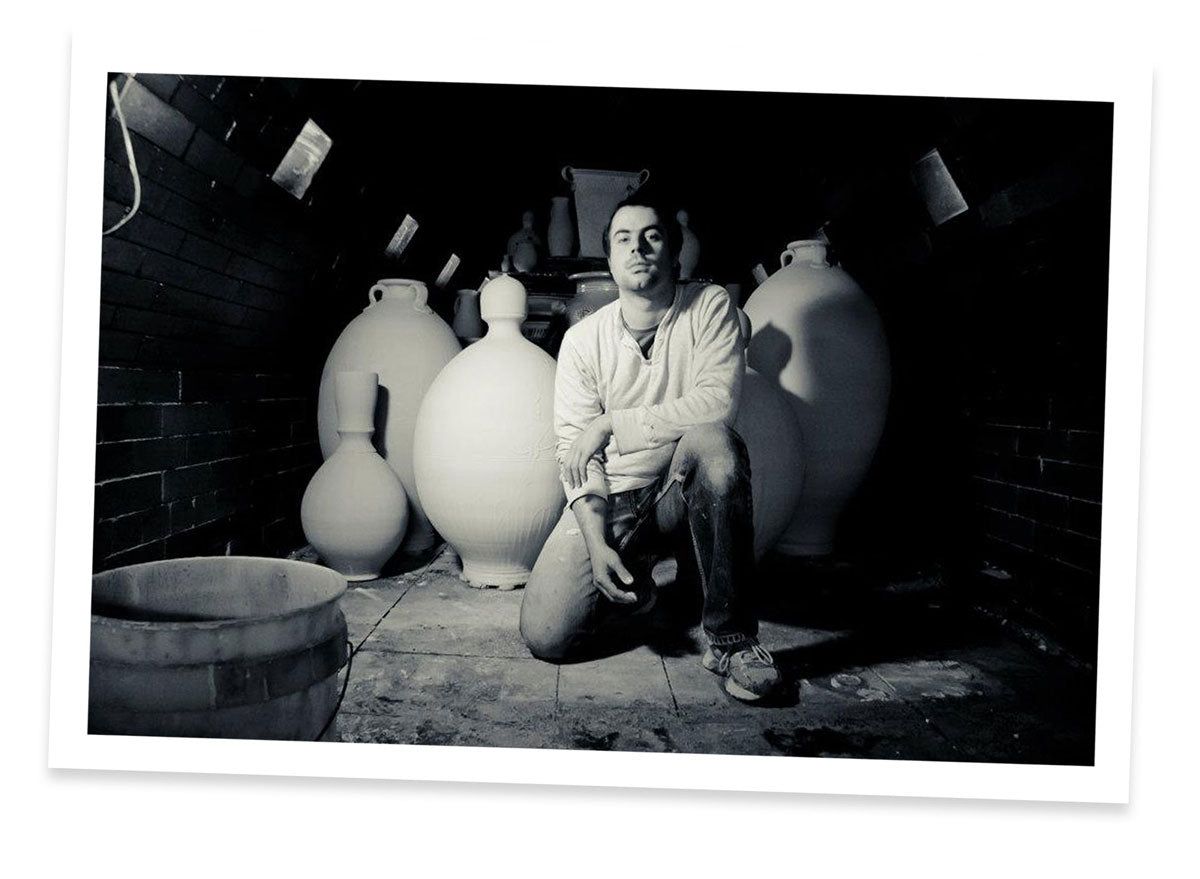

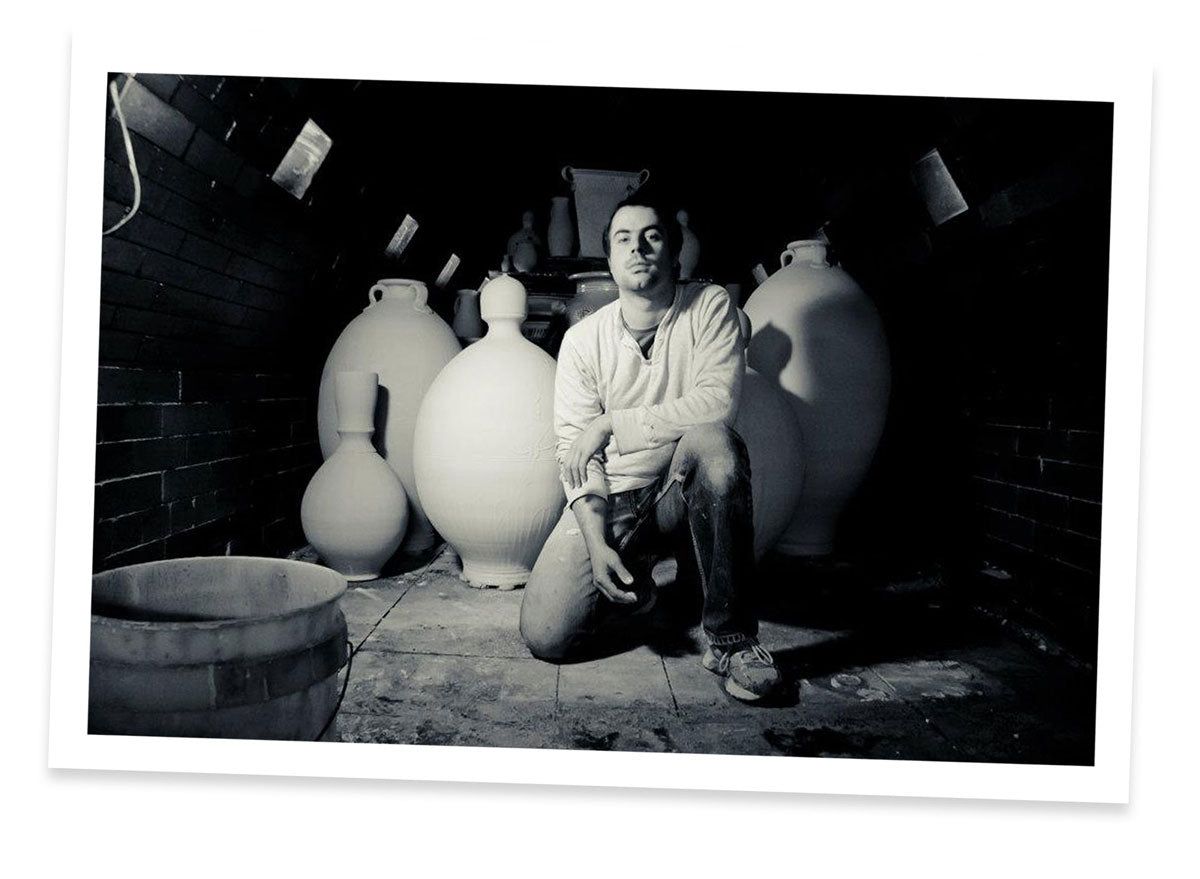

Why Is It Called East Fork?

Alex Matisse, East Fork’s founder, on how the company got its name and why it represents a “little private victory” for him.

Read more

Color Theory: Core Colors

Our Head of Design, Nicole Lissenden, shares the details of how we built our core color palette.

Read more

How We Make The Mug

Want to know everything there is to know about how we make The Mug? It’s your lucky day. Get the behind-the-scenes on how we make our iconic ceramic mug.

Read more

Update on How Our Pots Get Made

East Fork’s manufacturing floor stands on the precipice of a big change. We’re preparing to move to a new clay body and glaze recipe that’s been three years in the making.

Read more1/5