Black Mountain: We Are Mountaineers

This season, we introduced two new colors to our core collection—Blue Ridge and Black Mountain, named in celebration of our local region.

Journalist-historian Cynthia Greenlee has family roots in Black Mountain and will be leading us through an exploration of her Black Mountain—past, present, and future.

Read Part 1 here.

I grew up in a house of bookshelves stuffed with encyclopedia sets, Reader’s Digest abridged versions and medical diagnostic manuals. In our wood-paneled den, the top shelf of one bookshelf held my father’s serious books, placed out of reach from elementary-school fingers and minds: Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, Eldridge Cleavers’ Soul on Ice, Margaret Walker’s Jubilee, J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Shakespeare.

I wanted to read those verboten books, but I was just as captivated by the the bookshelf’s bottom cabinet, which contained notebook paper and my father’s Foxfire books. I was allowed to look at those, but warned not to damage or misplace them. He had a full set.

The legendary series of books that compiled Appalachian traditions had started when a teacher sent a class of teens to talk to their elders in their mountain communities. They documented many “old-timey” traditions that were disappearing or already long gone by 1972, when the first book appeared. Stories of everything from traditional hog killings to haints filled the 13 volumes, which spanned until 2004. With that long publishing run, the books left a huge footprint in the world of Appalachian studies.

I scoured the books for the occasional story about Black people, a fleck of pepper in a sea of salt (but not as easy to spot). For, as my fellow historian and friend, Dr. Jessica Wilkerson, noted recently in Southern Cultures, the Foxfire books fostered an idea of Appalachian elders as wholesome rural pioneers and their industriousness as a quality lacking in modern times and generation. And, of course, they were white.

Wilkerson wrote the books “sold a white ethnic identity that separated white Appalachians from skin privilege and the centuries-long history of American racism and domination, under renewed scrutiny in the crucible of the Black freedom struggle and 1970s liberation movements.” While the Foxfire books were inherently a lament about change, over almost three decades of publishing, little changed about their racial and demographic vision of the region.

Two years ago, I found what I’d been looking for — a simultaneous antidote to Foxfire’s unrelenting whiteness and a repository for the stories about Appalachian foodways that I heard, in snippets, as a nosy child and professionally nosy historian-journalist adult who craved my aunts’ stories as much as I craved hot dogs at the family pigouts.

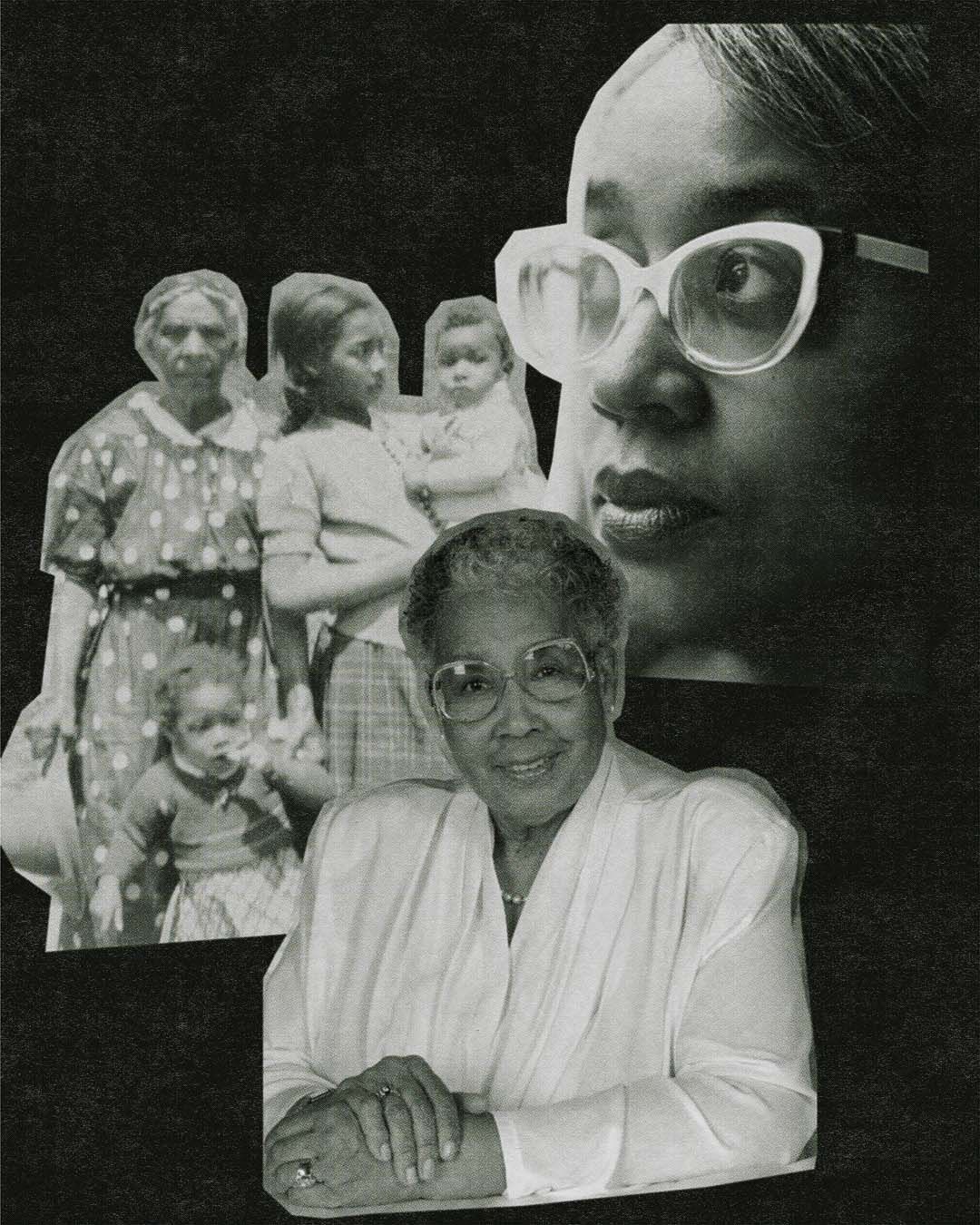

Several years ago, at age 89, Black Mountain-born retired teacher Mary Othella Burnette self-published an account of her life, Lige of the Black Walnut Tree: Growing Up Black in Southern Appalachia (available on Amazon in paperback and Kindle).

She did so because she didn’t see the Black communities of the mountains reflected in the historical literature of the region. And few accounts are written by people from those communities (there are a small but increasing number, such as the historian William H. Turner’s recent release, The Harlan Renaissance, about African-American life in Kentucky coalmine towns).

“People act like we weren’t here, and we’ve been here for centuries.” And what’s more, we weren’t hillbillies, she asserted, but “mountaineers.” She said the word like it tastes good in her mouth.

Full disclosure: We are distant cousins. Now 91, Burnette told me, via text from her home in southern Michigan, that her paternal grandmother was my paternal grandmother’s aunt. That took some genealogical unraveling; our entangled family tree has many branches, which once drooped with fruitful families of seven to 10 children, often many more.

Her memoir is full of real-life characters. Miss Emmaline washed the clothes of white customers over a sooty fire — no washer machine — and balanced their laundry baskets down curving roads on her head. Some of my relatives (and Burnette’s) make appearances. Her midwife grandmother, Mary Stepp Burnette Hayden (born around 1858), remembered someone reading the Emancipation Proclamation when she was just 5 years old. Slaveowners tried to squash the news of freedom, unsuccessfully, but they couldn’t stop the march of it when the Civil War ended. Burnette’s Granny only became a free person at age 7.

After her retirement, Burnette realized that she was an “elderly member of that vanishing society,” a cohort who had lived with a family or community members who had been enslaved.

“The land was everything” for that generation, Burnette said to me. Land was so important that the word appears 99 times in her slim volume. After the war, her aunt Phoebe, who had been enslaved, took a meager $10-a-month job in a hotel but saved enough to buy 2 acres of land. Many of the Burnettes bought adjoining plots, just big enough for a house and “to raise a crop of vegetables (often preserved by drying) to keep food on the table year-round.”

Decades before I ever ate at my relatives’ homes on Cragmont Road or ever wrote a word about food, the Black residents of Black Mountain knew a thing or two about coaxing food out of the land, and Lige of the Black Walnut Tree brims with tantalizing morsels of foodways knowledge. The titular walnut tree was to be protected at all costs. Local dialect pronounced “okra” as “okri.” Burnette’s mother baked bread from wheat they sometimes grew. Granny Hayden hacked away at sassafras trees for bark to steep into tea, and the young Mary Othella would carry satchels of corn to the local miller. Miss Hester would churn clabber and shape butter — deep gold or pale yellow, according to the cow’s diet and time of year — into a mold. This seemed like porch-to-kitchen magic then to the child Burnette once was and to me now. I confess, as a 1970s baby whose milk always arrived in grocery-store cartons or plastic jugs, I had to look up exactly what “clabber” was (naturally clotted sour milk).

Burnette’s “Papa” — Garland Alfred Andrew Burnette — was a master of seasonality and in tune with the terrain and what it had to offer. She wrote: “He knows all about the trees. He knows how to protect the budding peach tree from frost, and knows exactly when our newest apple tree will bear fruit. He knows all about the seasons and the soil, knows which seeds to plant or when to gather their crops by the sign of the moon, knows which seeds not to sow on the dark of the moon, when to rob the bee hives of honey, when to hunt certain animals, and that certain small animals ain’t fit to eat during months spelled without ‘R’s’ [pronounced “ar-rahs”] in their names.

Before foraging became fashion (I wrote a New York Times story about Black foragers that went viral), Burnette and playmates frolicked in a field, where they found arrowheads and nature’s delights: “ … We’d find little bunches of yellow-green ground cherries, sweeter than yellow or red tree cherries, or [Maypop] vines with dark green leaves. And hiding under the leaves we’d always find gourds, the same color as the leaves, soft and sweet inside, plants that had sprung up from old seeds or roots deep in the ground.”

As a Black journalist who often writes about food and agriculture, I delighted in these passages describing this bounteous place I thought I knew well, with its black walnut trees. I might not want to make molasses, but these stories were a testament to Black presence in Black Mountain, Western North Carolina, Appalachia, and once-rural America. They attest to Black use and stewardship of the environment. While it’s commonly and problematically assumed that Native or indigenous people are “naturally" connected to the land, there’s also a common belief that Black people, stereotypically labeled as an “urban” people post-Great Migration, revile the countryside. Or that we renounced agriculture as a profession or way of life because slavery once chained our forebears to toil on the land. Or that we see more beauty in concrete skyscrapers than a mountain clearing. That we don’t camp … I can go on and on.

That may be some people’s stories, but it’s not mine. I’m leery of romanticizing the life of Black mountaineers, as Foxfire did, but don’t we get to be pioneers and explorers too? I thought this, not long ago, when I heard about a stand of wild chanterelle mushrooms on public land a few miles from our family home in Black Mountain. I zipped up my boots and headed out, reminding myself to look out for police officers who think I’m not supposed to be there, doing something as innocuous as browsing for nature’s free stuff. And to pick sparingly and to leave some for those who would come behind me. Maybe one day, I’ll leave a story behind about that, too.